Should We Run Schools Like Businesses?

The last few years have seen a number of calls for schools to be more entrepreneurial. I think this is a classic case of lazy thinking that sounds good until some real analysis is done. Then its weaknesses are revealed.

The last few years have seen a number of calls for schools to be more entrepreneurial. I think this is a classic case of lazy thinking that sounds good until some real analysis is done. Then its weaknesses are revealed.

Listen to this post!

What do these proponents mean when they say “entrepreneurial?”

A recent Education Week piece lists the following, fairly typical, aspects of entrepreneurism. This list includes:

- negotiating partnerships with companies and outside organizations

- creating a brand and aggressively marketing it

- breaking with traditional operating methods

- thinking outside of the box

- being willing to take risks

What were schools doing instead?

The first aspect of the sloppy thinking is the assumption that schools haven’t been doing any of this. Outside partnerships have long been a staple as a way to raise money, certain schools have been known for their music, theatre, science programs etc which they have promoted in the community.

The arguments the proponents of school entrepreneurialism should be making is why schools should be doing more of what they have always done in this regard. But none of the arguments I have read have impressed me at all.

Should schools brand and market themselves?

I have read that schools should be doing this because of competition from other schools in an era of a certain amount of school choice. But given that we have more school choice because of the very same people who are advocating entrepreneurism, this seems a circular argument. Negotiating more extensive relationships with outside organizations might make sense, but it is hardly some kind of magic potion to cure what ails schools.

I have read that schools should be doing this because of competition from other schools in an era of a certain amount of school choice. But given that we have more school choice because of the very same people who are advocating entrepreneurism, this seems a circular argument. Negotiating more extensive relationships with outside organizations might make sense, but it is hardly some kind of magic potion to cure what ails schools.

Should principals take risks?

The argument that principals should think outside the box and take risks is the one that really annoys me. The argument for entrepreneurism comes from the same people who advocate extensive testing and assessments. The demand for testing and assessments severely limits the ability of any given principal to “think outside the box and take risks.”

Let me give you a specific example: “Unschooling.”

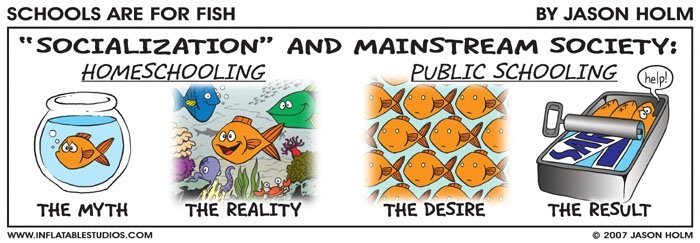

Many advocates of homeschooling believe in a philosophy called “unschooling” . This is based on the work of John Holt from the 1960’s and places like Summerhill school in England. Unschooling, about which I have some mixed feelings, believes in having the child take the lead. There is no set curriculum, but rather the curriculum is set by the child’s interests. The parent or teacher is much more of a facilitator than someone who dispenses knowledge.

Unschooling emphatically rejects the idea of certain cognitive accomplishments being done by a certain time frame. So unschooling parents that I know don’t worry if their child can’t read and is 9 years old, or can’t add, or hasn’t memorized multiplication tables by a certain age. They certainly completely reject standardized testing of any sort.

Click to see the article “unschooling fact vs myth”

Can Unschooling be a school??

Now, it would be highly entrepreneurial to establish a public school based on the philosophy of unschooling. Raise your hand if you think it would get funded. Raise your hand if you think that the “education reformers” have unschooling in mind as an example of entrepreneurial schools. Yeah, me neither.

The advocates of entrepreneurism in schools are also missing a series of fundamental facts about being an entrepreneur.

Fact ONE about entrepreneurs

First fact is that most entrepreneurs fail. According to a variety of students, more than 60% of business start ups fail in their first six years. Businesses that are still open but not particularly financially successful count as successes. Would we accept that kind of failure rate for schools?

I hope not.

Why?

Because when an individual business fails, the people most hurt are the people who started it, and they knowingly took the risk of starting the business. Entrepreneurs sign up for failure. But kids don’t.

Fact TWO about entrepreneurs

Second fact is that entrepreneurs have way more control over how they run their enterprises than principals do. I can decide that CITE won’t pursue doing bar exam courses for lawyers, but a school can’t decide that they won’t teach science.

Schools have a series of stakeholders because they are a public institution. Businesses are public in the aggregate, but not in the individual sense. There’s no harm done if CITE doesn’t do bar exam prep courses because someone else will. But a school not teaching science means that the kids attending that school don’t get taught science.

We as a society aren’t willing to take that risk.

What is a better model than a business?

What metaphor might work better than principals being entrepreneurs? If you ask Rich Hawkins who leads the College of St. Rose/CITE Ed Admin program, he would say that we should view principals as leaders. I might use the metaphor of manager. I think the difference between Rich and I is a question of how much autonomy the principal has.

Principal as manager

A manager is largely responsible for the excellent execution of a given set of priorities that are set by some kind of structure that is hierarchically above him or her. What we want from our principals is that they create a climate in which our children learn as well as they possibly can. What we want from managers is that their department perform their assigned tasks as well as possible.

A manager is largely responsible for the excellent execution of a given set of priorities that are set by some kind of structure that is hierarchically above him or her. What we want from our principals is that they create a climate in which our children learn as well as they possibly can. What we want from managers is that their department perform their assigned tasks as well as possible.

Notice the similarity?

A manager both creates or reinforces a certain structure and empowers their workers to address problems as they arise. That’s exactly what a principal does with his or her teachers. Managers often get hamstrung by some stupidity from higher ups who don’t really understand what happens on the level at which the managers and his or her team work.

Sound familiar?

If our principals have more autonomy, then leader might be a better metaphor, because the core job of a leader is to develop a clear vision which everyone owns and works towards. If a person is a manager, that vision is set above his or her pay grade, if they are a leader, they have responsibility for that vision.

What about innovation?

One last point. The lack of innovation isn’t a core problem for our schools, as if there is some magic out there waiting to be discovered or invented. In fact, this belief that there is some kind of magic bullet just waiting to be discovered and implemented is part of the problem. Sure I am a fan of new ideas such as differentiated instruction and social-emotional learning. But poor execution because of too much change in leadership and policies that simply can’t be implemented well are much bigger problems.

Jared Gellert is the executive director of CITE.

CITE is the Center for Integrated Training and Education . For over 25 years, CITE has and continues to train TEACHERS (Early Childhood, Literacy, Special Ed, Grad Courses, DASA); COUNSELORS (School, Mental Health Masters, Advanced Certificate); and ADMINISTRATORS (SBL, SDL, Public Admin, Online PhD) in all five boroughs of NYC, Yonkers, and Long Island.

What question can we answer for you? 877-922-2483